You wake up and look around. You are in a strange place. You’re not sure how you got there. You don’t remember your clothes, or for that matter, anything at all. Welcome to the narrative of the movie Memento by filmmaker Christopher Nolan, one of my favorite movies of all-time. In this film, we follow Leonard Shelby, an insurance investigator who is trying to solve the murder of his wife. There is one enormous wrinkle in the story, however. Leonard was with his wife when she was attacked and was himself hit over the head, causing serious brain trauma. Now he is unable to form new memories, and so every twenty minutes or so, his memory fades and his mind is like a blank slate. Everything that he knew from after the moment of the accident is forgotten. In terms of knowledge, he begins anew.

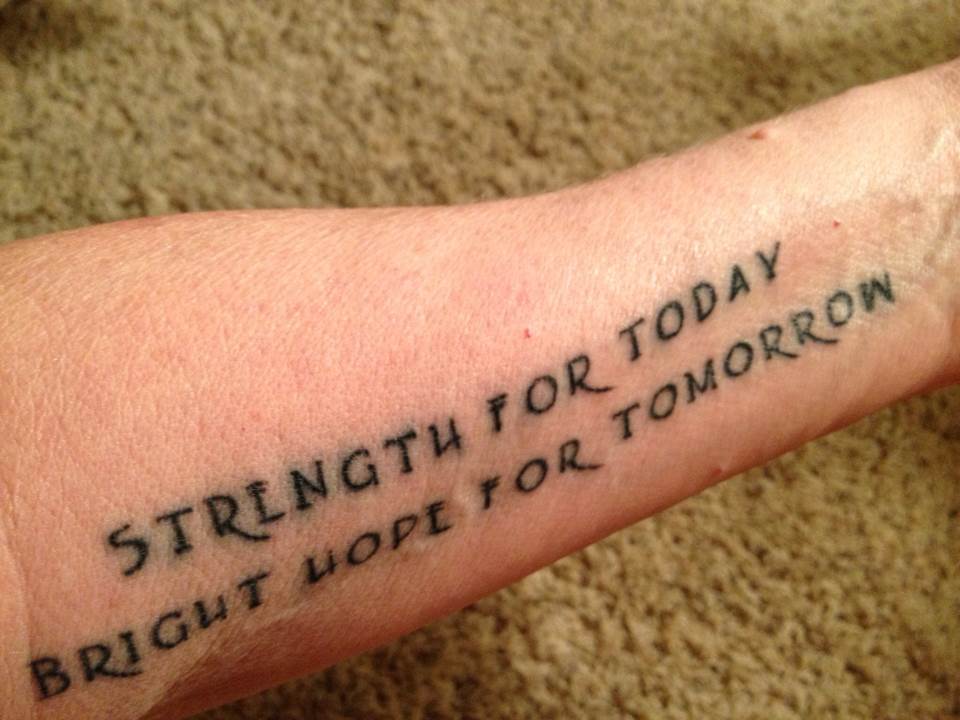

Leonard has realized that if he is going to solve the murder, then he must find a way to accumulate knowledge, something that his brain is unable to do. Hence, he makes a practice of writing himself notes and then tattooing the facts of the case all over his body. His body becomes a gruesome body of knowledge, a record of what he believes are absolute truths about his wife’s attacker. He places faith in his own handwriting, his copious notes and the conclusions etched all over his body like the Ten Commandments. Along the way, we discover that these truths are themselves compromised by his inability to remember. We find ourselves asking, “How do I know what I know? If I cannot really know anything, how can I trust anyone?”

Faith, to a certain degree, is built on experiential knowledge. You know God because over the course of your life you have experienced God. That is not to say that God isn’t revealed in other ways, like in the natural world or in sacred books like the Bible. But even those written records, those tiny scraps of paper that were jotted down at a moment in time, are grounded in the experiences of people. They knew God because they encountered Him in the context of a story, and then wrote about it. For the most part, the doctrine came later. And so, experiences of God over time become building blocks of faith. Devotion relies on a long memory.

Unfortunately, most of us struggle with memory problems, not unlike Leonard. When I find myself stuck in a moment, as I do now, I return to a book of laments found in the Bible, and resonate with what I find there. The people of Jerusalem had been experiencing a truly horrific siege by the Babylonians. As I search for hope in my own story, I welcome the wisdom of the author: if I want to follow God into the future, then I need to remember who God has been in the past.

1) Milestones of Mercy

Lamentations is comprised of five chapters of the darkest poetry that you’ll ever read, including the stacks of journals that you filled as a sophomore in high school. At the very center of that ordeal, however, is a shining beacon of hope, a few lines so profound that they stand out like a brilliant star against the night sky. “Through the Lord’s mercies we are not consumed, because His compassions fail not. They are new every morning; great is Your faithfulness.”

How in the world is this author able to make this extraordinary statement? They are not consumed? If the poetry is not purely hyperbole, then the starvation was so intense in the city that people were cooking their own children for food. What in his experience allows him to make this audacious statement of faith? Where does he place this bold hope for their welfare in the midst of such savage uncertainty? Clearly, he places his hope in the past, in whom he has experienced God to be.

Faithfulness, after all, is something that you come to know about someone over time. It is not something that you discover on your first or second or third meeting, but on your ninth or tenth. It is an accumulation of knowledge about the character of someone, and you gain that insight in the midst of real life, in your experiences. You discover it when they show up to help you move, or cover a bill that you are unable to pay, or remain committed to the marital vows that you both made.

People who know God establish milestones of mercy in their lives. They tattoo truth about God onto their bodies. They make monuments of these moments when God shows up to rescue them. Why? Because we all have a memory problem, just like Leonard. It is easy to doubt God when you’re besieged by the Babylonians. If you want to have hope, then you must etch those remembrances onto your heart.

2) Expectations of Grace

The author makes an even bolder statement in the verses that follow, beginning each of three sentences with the word “good” in order to make a point. “Good” is the Lord to those who wait for Him. “Good” that one should hope and wait quietly for His salvation. “Good” to bear “the yoke in his youth.” All of these statements build upon one another in an unnerving way to make a point that is true, but rarely comfortable: God’s goodness doesn’t always look good on the surface. At times, it means that you sit alone and shut up, that you “put your mouth in the dirt,” or that you give your “cheek to the one who strikes” you. But is this goodness?

As I write, there is a homeless man shuffling around on the street outside the window of the coffee shop where I am seated. His clothes are dirty and tattered. His hair is matted into unintentional dreadlocks. His skin is dark brown, not from pigment but from grime—from being in the dirt—and constant exposure to the sun. Pointing angrily at the ground, he is arguing with some unseen person, re-litigating some struggle or conflict from his past that continues to haunt him. Trapped in the chasm of his own mind, he is reliving an imaginary conversation because his mind has become afflicted. He is severely broken, stuck in this dreadful moment, like a turntable with a needle that keeps skipping back. This is what happens when you live with the Babylonians outside your gates for too long. This is what happens when you forget to remember what you once knew. Is this really goodness?

No. No, it is not. We find “goodness” in the previous verses. The writer says, “The Lord is my portion…therefore I hope in Him!” A portion is an inheritance. It is a substantial gift that you receive after a long wait, not because of deserving, but because of grace. The person who knows God has come to realize that He is faithful to bless those who wait on Him—not because they have earned it, not as some kind of reward—but because of grace. We have an expectation of grace.

Listen, I don’t really know what it looks like to wait on God. I don’t know if you shuffle around on the sidewalk having conversations with yourself. As I wait upon God in my own life, I must confess that prayer often feels exactly like that to me. I don’t know if you race around trying to solve the puzzle of what happened to your life, the unfortunate event that led you to this impasse. I find myself doing quite a bit of that as well. But one thing I do know: you cling to an expectation of grace. You say to yourself, “Even if my entire inheritance is just a closer walk with God, it is enough.” You tattoo on your body, “Blessed are those who wait for Him.”

3) A Discipline of Remembrance

We could stop right there and it would be enough, but there is more. You see, power is at the very heart of this question. On the one hand, the adversaries are outside the gates and they are flexing their power, causing these horrendous things to occur in the city. The author has a direct comment for them: the Lord does not approve. It is never justified to crush prisoners and turn aside justice before God. But on the other: “Who is he who speaks and it comes to pass, when the Lord has not commanded it? Is it not from the mouth of the Most High that woe and well-being proceed?” He recognizes this incredibly painful conclusion. Suffering exists in the world because on some level, God has allowed it to happen.

While he could dwell on the problem of evil, the author has a different response. He urges his community, “Let us search out and examine our ways, and turn back to the Lord.” Honestly, I am a little tired of asking whether God is angry. I realize in that time period, it was natural. They were always seeking a cause-and-effect in their lives, as if a bad harvest signaled that you had displeased the gods, and a good one implied that you were righteous. Certainly, there is some of that mindset here. But I think he is actually asking a much deeper question, one that makes room for grace: “What do you want me to remember, Lord? What have I forgotten?”

The journey of faith involves, more than anything, a discipline of remembrance. Let’s face it. The reality is that we are all memory-compromised, whether or not we have suffered brain trauma. We ignore our own transgressions, but magnify in our minds the sins of others. We become obsessed with what has been taken away from us, but overlook the grace left at our doorstep. We bask in our privilege, but chalk up our prosperity to our own industry. In the process, we tattoo on our souls truths that are not true because we do not see clearly or know fully. And so God in His mercy uses His power to prompt a deeper examination of our lives.

What would a discipline of remembrance look like? The answer might surprise you. Honestly, I think that we need to celebrate more. We need to recognize those milestones of mercy on a regular basis in our lives, heaping more stones upon them as the years go by, so that they loom larger in our memories, not smaller. We need to form a community that will help one another to remember God. We also need to do a better job of lamenting together, I think. Let adversity prompt us to examine ourselves on a regular basis, not in fits and starts as the circumstances demand. If we are memory-compromised, let’s draw together in a healthy way to help one another remember grace. Because you need a long memory to follow God.

Daniel Radmacher © 2017