She sat perched erect on the piano bench, like a bird on a wire, except with all the joy and freedom removed. Her face looked brittle, jaw set like stone, as if it would shatter to pieces if she smiled. To my eye, she had seemed ready and willing to squash my dreams from the first moment we met, like a Pygmalion who didn’t fall in love with his creation but grew to hate it and kept chipping away pieces until there was nothing left.

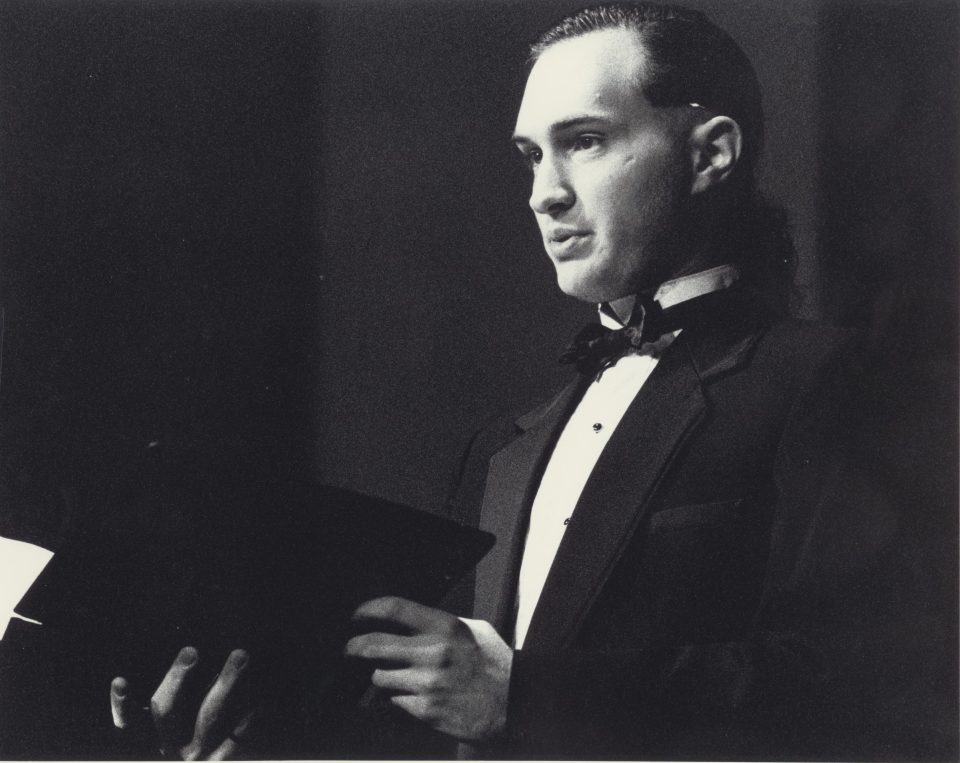

I was in the last years of my undergraduate vocal training at a small private college in southern California, intent on becoming an opera singer, single-mindedly dedicated to filling in the shadow that my ego had thrown on the wall in front of me. And that wall had sat there on that piano bench in front of me for two torturous years—unmoving, unsympathetic and singularly unimpressed by me. How could that possibly be? I had been lauded for my voice and ability from an early age, receiving accolades from my teachers and directors alike, singing in choirs well above my age, winning an Oregon State Solo competition. What was wrong with her? How could she not see me?

From the beginning, it seemed like her mission—nay, her joy—was to break me down, strip me of self-esteem and confidence, reinforce how very ordinary I was, when I had always known differently. So we fought from day one. Nothing was good enough. My every note was somehow broken—lacking something. I failed the test at every lesson. Her “instruction” was to me a knothole that I was being drug through, all the while attempting to maintain my spark while yet playing her game. And I was losing.

We finally came to verbal blows after my junior recital, when I—with my usual flare—had contradicted her direct order to not use props on stage. During the performance, I had drawn from my pocket a little journal to better illustrate Mozart’s “catalogue aria” from Don Giovanni, in which Leporello goes through the salacious diary of his master’s many paramours in order to belittle the latest target. And she responded even worse than Zerlina had, dressing me down and threatening to expel me from the music program for my infraction. I only survived by abasing myself.

But here we sat now, with the shoe on the other foot. After my catastrophic misdeed, other faculty had—without my knowledge—gone to bat for me, arguing my case against her. Another student with similar troubles—whose father was a well-heeled donor—had gone to the very top, making a case that she should be disciplined in some way. She was telling me about it in her studio on that piano bench, closer to tears than I could have imagined. She asked if I agreed with their verdict. She said, “I wanted to ask you—needed to find out…what you think…where you stand…if you agree.”

She was asking me to accuse, convict and sentence herself, something I would have relished, even might have rehearsed only an hour before. Now I sat dumbfounded. I had no retorts on my lips, no scorn in my voice, no hatred in my eyes or mind. Only a bitter taste in my mouth, and it seemed as if I could not speak. She waited for my response—preparing for my condemnation, my honeyed virulence, but I could give her neither.

Something inside of me let go, like a taut rope that has been holding up the scenery for years upon years. I was revealed to myself by the raw anguish of another, and I realized my mistake. Honestly, I don’t remember exactly what I said in that moment, but thirty years later, I can articulate the truth that has been revealed to me since: “In days past, I hated you, found every reason to dismiss you. I thought I was very important then, but I’m starting to realize that I don’t see myself very clearly. All I know right now is that I must find a way to love singing, love this voice—love myself—again…”

Comeuppance. One of my favorite words. I learned it from a high school literature teacher, who loved to use it in describing the characters from the Iliad. I relished that word back then but was about to learn its bitterness. Everything fell apart in an instant, faster than a dying man sinks to his knees in a cowboy shoot-out. My pre-recital, a test for the entire school of music faculty to determine whether I could perform, was on for three days hence. Suddenly and calmly, I lost my voice. I don’t mean that I lost my voice in the usual sense. I was not experiencing a bout with laryngitis or some other mystical singer’s ailment. Rather, it was as if my years of training, technique and rehearsal had vanished. My voice and my strength were gone, as though they had never existed.

I failed my pre-recital miserably. I still remember one of the “jury” forms from the only other voice professor in the school who I thought disliked me more than her—a famous bass soloist in the area. I am quoting him verbatim: “You’ll never be a professional singer unless you…” The words stuck like a bone in my throat, and I couldn’t swallow anything else that followed, even things that were accurate. Perhaps his words should never have been written down at all but spoken to me in private. Perhaps I wouldn’t have been able to hear him, regardless. Looking back, I forgive him. But I stuck the form in my copy of Don Giovanni and departed the building, completely deflated. Empty inside.

I sat on my bed stunned, when I put down the receiver that had carried the unfortunate news from my teacher. In the interim, we had begun to forge a working relationship that was respectful and cooperative, and so she called me in person. Failing this step in the process would mean that I wouldn’t graduate, that I would have to start from scratch and spend yet another year under her tutelage. But what was worse is that I had completely lost my identity, my sense of who exactly I was.

She had said, “I am willing to help you in this—I am willing to fight for you. But I must know if you are able to fight.” I had responded that I wasn’t sure if had any fight left in me, choking back the tears. I sat and prayed for three days. Not the kind of prayers that you often hear in the movies. Not the prayers of leverage, or “you do this for me and I’ll do that for You.” These were the kind of prayers that feature more questions, ones that can’t be answered with a “yes” or “no.” Mostly they were just prayers of surrender.

I met with her three days later, and said, “Yes, let’s fight.” I began to work, pulling repertoire out of the dark closets and forgotten corners of my rehearsal hours. Together, we ended up replacing about three quarters of an hour of material with music that was less demanding, and which I already knew. I followed her instructions to the letter, as I had never done before. She knocked down department doors to get me a second pre-recital with just the head of the department there to adjudicate. She scared up a date for my recital seven days before my graduation ceremony. And slowly, my voice came back, not as strong as before, but good enough. I was given the green light, gave a passable recital and graduated—all of this over the course of one month.

I walked away from classical voice for three years, taking a job in the record industry instead. And then, I began to work my way back, slowly and surely, working with a new teacher, and then another, listening more than I ever had before. Joy, freedom and love have returned to music, and now—thanks to my current teacher—I can say that I have been given the voice I always wanted to have. But I am not the same—thank God.

A few years ago, I pulled out my score of Don Giovanni, having completely forgotten what was stuffed inside. My current teacher and I were revisiting old material, and on a lark, I dug it out of storage and brought it with me, setting it on the piano in front of him. He is a consummate professional—as insistent on excellence and musicianship as every other teacher that I have worked with. And yet, I am greeted with a warm embrace, like an old friend, like I am loved. Opening the score, the pages from my jury form dropped out in front of him, and when I saw what they were, I was ashamed. I wanted to shrink away, to hide somewhere in the embarrassment. What would he think of me? What did I think of me? It was like the shadow of a nightmare was arising from the past, and I was about to be swallowed up by who I used to be. He casually unfolded the forms, read them, and knowingly said with a smile, “Well, that’s not talking about you, now is it?”

Well…is it?

(C) 2024 Daniel Radmacher